New maps expose hidden facts on herders and rangelands

First efforts to assemble vital evidence about pastoral people and rangelands

By Vanessa Meadu

If we can’t map it, we can’t manage it – and until now, pastoral people and rangelands have been largely unmapped. As a result, pastoralist issues have attracted less political attention and investment than well-mapped areas such as forests. At worst, poor evidence has led to interventions that have harmed rather than helped pastoral people.

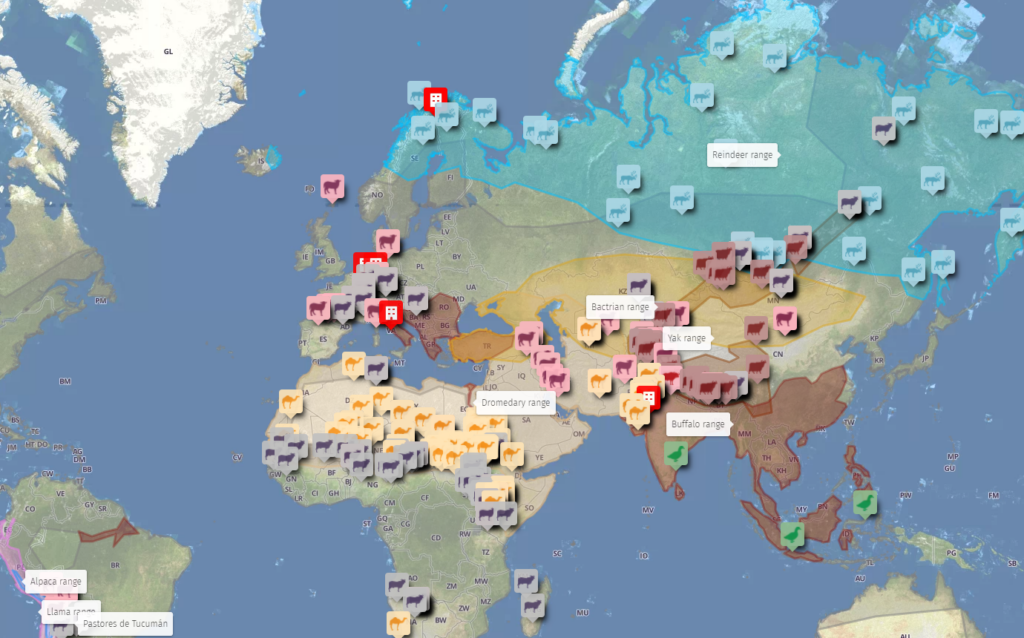

Two new initiatives are compiling valuable evidence about pastoralists and rangelands. The global Rangelands Atlas and the Pastoralist Map both aim to improve understanding about the complex systems where pastoral people rear and graze their animals. Project leaders hope better data on pastoralists and rangelands will debunk harmful myths about the impacts of pastoralism on ecosystems, and inform better decisions. Both maps are designed to inform international efforts to combat climate change and desertification, enhance biodiversity, and sustainably transform food systems.

“Pastoralists are crying for more attention, more care, more investment” said Ibrahim Thiaw, Executive Secretary of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). “Mapping rangelands is the first step towards ensuring these areas are sustainably managed,” he told the audience at the recent Rangelands Atlas launch event.

The Rangelands Atlas at a glance

The Rangelands Atlas focuses on the vast areas of grasses, shrubs and vegetation that make up 54% of the world’s terrestrial surface. These areas may be grazed by livestock and wildlife and are essential for pastoralist livelihoods. The initial set of 16 maps draw upon existing global datasets to show how issues such as climate change, biodiversity, land degradation and deforestation play out in rangelands. They reveal the social and economic value of rangeland areas, showing 45% of the world’s terrestrial surface is in areas used for ruminant livestock production. They also offer a platform for local voices: users can explore how a particular community is responding to the changes described in each map.

“The maps are helping us fill significant data gaps and inconsistencies,” explained Fiona Flintan, a Senior Scientist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) who is one of the driving forces behind the Atlas as well as the Global Rangelands Data Platform. Flintan and her team won the 2020 CGIAR Big Data Inspire Challenge, which co-funded the first phase of work. “We are building a knowledge base on the distribution, status, risks, changes and opportunities for restoring or building resilience in rangeland communities,” she said. Future developments will include land matrix data and conflict mapping. National level data will be added once the broader Global Rangelands Data Platform is established.

The Pastoralist Map at a glance

The Pastoralist Map exposes the human side of livestock-keeping. “We want to put a face on the hundreds of thousands of pastoral communities which have remained largely invisible,” said Ilse Köhler-Rollefson, Senior Advisor at the League for Pastoral People and Endogenous Livestock Development, which spearheads the project.

One of the goals is to demonstrate how pastoralist people produce food in tune with nature. “We hope this leads to an acknowledgment of the value of pastoralism, and clarifies the enormous urgency of supporting these systems, especially in light of the upcoming UN Food Systems Summit,” explained Köhler-Rollefson.

The map shows areas where different animal species are found, including reindeer, camels, yaks and llamas. Users can learn about more than 200 different communities that manage pastoral animals, from camel-breeding Rebari people in Rajasthan, India to urban shepherds whose animals mow grass around Paris. Many of these groups have not been counted before.

Much of the information on the Pastoralist Map is derived from the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung Foundation 2014 Meat Atlas, which was builds on the 2001 UN Food and Agriculture Organization report Pastoralism in the new millennium. Data also comes from ongoing efforts by the League for Pastoral Peoples to account for pastoralists, and from Wikipedia. The project team is now looking into the scientific literature to obtain more detailed information.

Partners at a recent launch event explained how the Pastoralist Map would help their work. “Better understanding of pastoralists will translate into improvements of how pastoralists are perceived, and to reorienting practices,” said Pablo Manzano of the Global Integrative Pastoralist Program, which is developing indicators to reconstruct pastoralist trajectories over time. He explained that the map will contribute to a more holistic understanding of pastoralism: “We need to count pastoralists and their advocates. The map is key for this.”

Working together for impact

Both projects offer tools for ensuring the that pastoral people and rangelands can contribute to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and the two teams are exploring linkages between their complementary efforts. “There are important synergies between the Pastoralist Map’s focus on people and the Rangeland Atlas’ focus on ecosystems,” explains Ilse Köhler-Rollefson.

Get involved!

If you have data or information that could improve these maps, please contact the project coordinators.

• Rangelands Atlas: Please contact Fiona Flintan (ILRI) with suggestions for global datasets and maps on rangelands that can be added to the Atlas. National datasets are not currently being added to the map.

• Pastoralist Map: Contact the League of Pastoral Peoples to schedule a tutorial for entering data for the map.

More information

The Rangelands Atlas is a collaboration between the International Land Coalition, the Rangelands Global Initiative, the International Livestock Research Institute, the UN Environment Programme, The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, WWF, IUCN and the global Rangelands Initiative of the International Land Coalition.

The Pastoralist Map is a joint effort between the League for Pastoral People and Endogenous Livestock Development, the LIFE Network, MISEREOR, the International Union for Biological Sciences, and the Helsinki Institute of Sustainability Science

Vanessa Meadu is Communications and Knowledge Exchange Specialist for SEBI Livestock, the Centre for Supporting Evidence Intervention in Livestock. SEBI Livestock manages livestockdata.org on behalf of the Livestock Data for Decisions (LD4D) Community of Practice.

Header image: Camels transporting salt harvested from the Danakil Depression, Afar, Ethiopia (Photo credit: ILRI/Fiona Flintan) (source)